By Lord Fiifi Quayle and Emmanuel DeGraft Johnson

A press conference by the Minority in Parliament, seeking to cast doubt on the operations of GoldBod has reopened an old debate. But beneath the noise lies a deeper and largely untold story_one that places GoldBod not as a problem, but as a corrective force in Ghana’s long struggle to protect its natural wealth from capture by narrow private interests.

To understand the significance of GoldBod and the Big Push, Ghanaians must revisit a critical moment in recent economic history: a period when the very royalties that now support roads, highways and strategic infrastructure were on the brink of being quietly transferred out of effective public control.

At the heart of that moment was the controversial Agyapa Royalties transaction.

The royalties that almost slipped away

Only a few years ago, the financial backbone of today’s Big Push_the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) and the Minerals Development Fund (MDF), derived largely from gold royalties and petroleum revenues, faced an existential threat. Through the proposed Agyapa Royalties deal, future gold royalty streams were to be monetised and transferred into a foreign-registered Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), raising profound questions about sovereignty, transparency and long-term national interest.

Under the plan, the Minerals Income Investment Fund (MIIF) would have assigned rights to future revenues from 48 major gold mining leases to Agyapa Royalties Limited (ARL). In return, Ghana was to receive an upfront payment estimated between US$500 million and US$750 million, with ARL later listing on stock exchanges in Ghana and London.

On the surface, it was presented as financial innovation, turning future income into immediate capital. In reality, critics warned that it was a deeply undervalued and opaque transaction that risked diverting billions of dollars in future public revenue into structures designed to benefit a few.

Counting the true cost

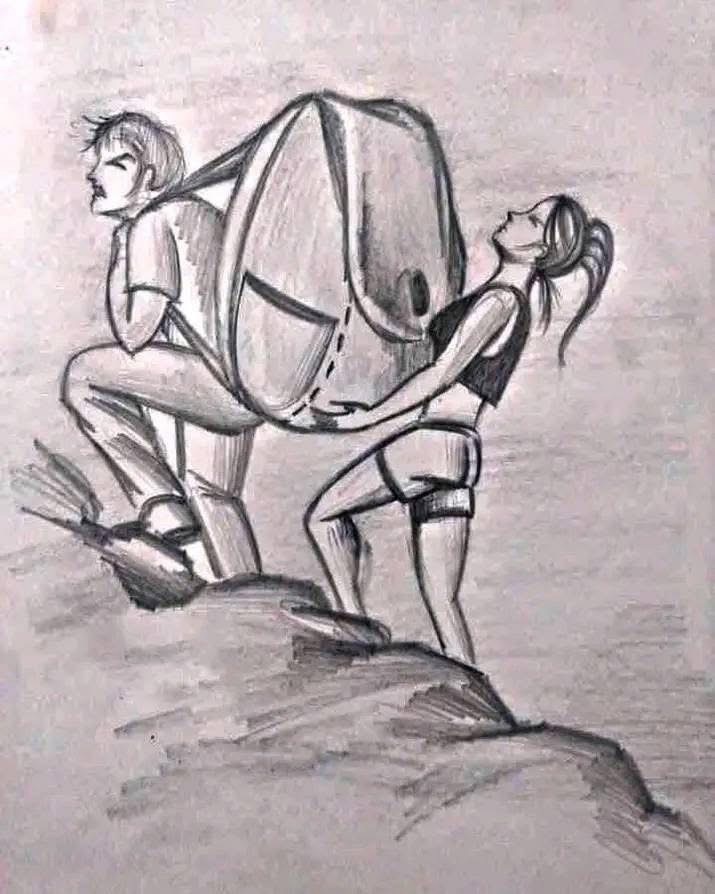

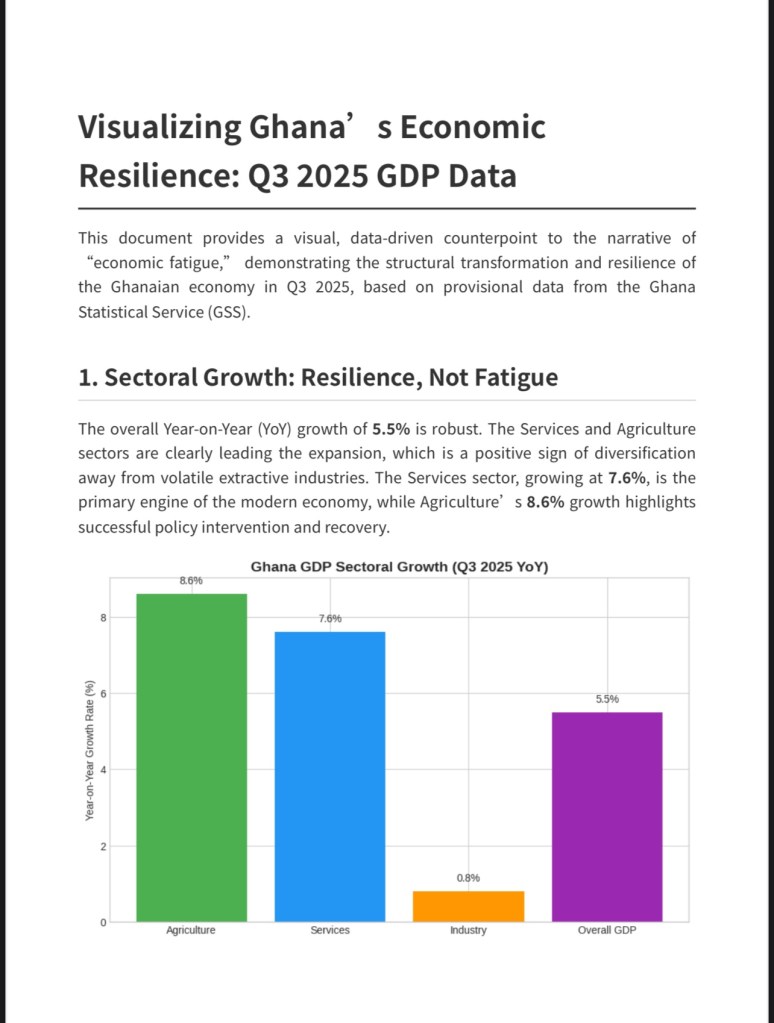

Ghana remains one of the world’s leading gold producers. In 2025 alone, gold exports, excluding most large-scale mining, are estimated at roughly US$11 billion. Royalties on gold production range between 3 and 6 per cent.

Using conservative assumptions:

• At US$10 billion in annual gold exports,

• With an average royalty rate of 4.5 per cent,

• Ghana would earn about US$450 million a year in royalties,

• Or US$4.5 billion over a decade.

Against this backdrop, the proposal to exchange long-term royalty rights—potentially in perpetuity—for a one-off payment of US$500–750 million represented a staggering loss of value, estimated by analysts at between 80 and 90 per cent.

Independent assessments suggested that the long-term value of the royalties could run into several billions of dollars, with some valuations placing the worth of a minority stake in Agyapa well above US$1.4 billion at prevailing gold prices at the time.

Governance, secrecy and conflict concerns

Equally troubling was the proposed structure. Agyapa was to be incorporated in Jersey, a jurisdiction known for secrecy and tax advantages. Draft legal provisions reportedly included stability clauses that could have limited Ghana’s ability to reform or exit the arrangement, even if it proved harmful. Critics warned that future governments and even the President, could find their hands tied.

Civil society organisations, legal scholars and policy analysts repeatedly demanded full disclosure, arguing that Parliament and the public were being asked to approve a deal whose true beneficiaries were unclear. Allegations of cronyism and conflicts of interest further inflamed public concern, prompting investigations by state institutions.

By the time public pressure forced a suspension and review of the transaction, nearly US$12 million had already been spent on preparatory work and consultancy fees, expenditure many described as wasteful, with little to show in return.

Why GoldBod changes the story

It is against this backdrop that GoldBod must be assessed. The institution represents a shift away from opaque financial engineering towards direct state stewardship of gold resources, ensuring that value is retained within the public domain and channelled into national development.

GoldBod’s operations, together with the ABFA framework, now underpin flagship initiatives such as the Big Push, financing highways, bridges and productive infrastructure across the country. These are not abstract accounting exercises; they are visible assets transforming lives and markets.

The irony is hard to miss. Some of the loudest critics of GoldBod today were silent, or at best indifferent, when Ghana’s future gold income was nearly sold off wholesale. Having failed to secure that transfer, they now question the very projects made possible by the proper utilisation of those same royalties.

A lesson Ghana must not forget

The Agyapa episode stands as a cautionary tale. Natural resource wealth is only as valuable as the governance systems that protect it. Without transparency, accountability and national control, a country risks trading tomorrow’s prosperity for today’s crumbs.

GoldBod, whatever its challenges, emerged in response to that hard lesson. It symbolises a determination to keep Ghana’s gold working for Ghanaians_not locked away in distant financial vehicles, but invested in roads, schools, hospitals and long-term economic resilience.

In this light, the current debate should rise above partisan point-scoring. The real question is not whether GoldBod should exist, but whether Ghana is prepared to once again flirt with arrangements that place private gain above the national interest. History has already shown the cost of that mistake.

Ghana Must Work Again