By Lord Fiifi Quayle

In democratic politics, the most consequential battles are rarely fought at the ballot box. The fight is fought earlier, in quiet places: within party constitutions, in unwritten norms, handshakes, and in the moral choices leaders make when the law still gives them room to operate. Ghana, and particularly the National Democratic Congress (NDC), now stands at such a moment.

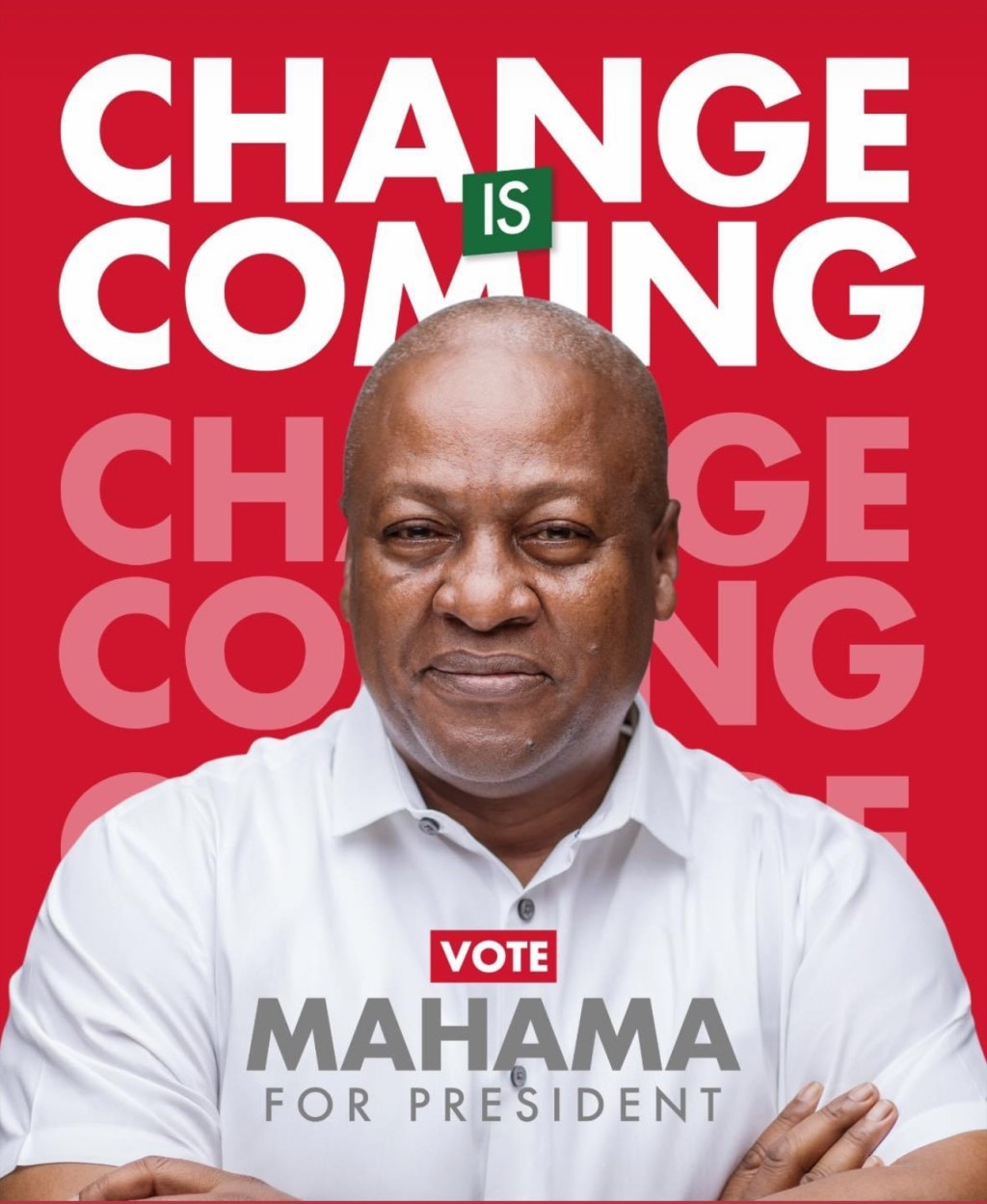

The argument against a third presidential bid by John Dramani Mahama is not, at its core, about his competence, popularity, or legacy. It is about principle: party principle, constitutional principle, democratic principle, and civic responsibility. On all four counts, the case against a third run is compelling.

The NDC and the Discipline of Precedent

The NDC is a party born out of revolution but sustained by restraint. Its founder, Jerry John Rawlings, wielded immense political authority at the height of his power. He could have rewritten internal party rules to extend his dominance. He did not. Instead, he submitted himself to a term limit and, in doing so, set a precedent that has quietly but firmly guiding the party’s internal democratic culture.

That precedent has not been ambiguous. Over the months, it has been reiterated by the party chairman and general secretary as a foundational principle: leadership must rotate, ambition must yield to institutional continuity, and no individual is bigger than the party. To go against this understanding would not merely be a procedural adjustment; it would amount to a repudiation of the NDC’s own moral architecture.

Political parties survive not because they always win elections, but because they are predictable in their values. Once a party signals that its rules bend for its most powerful figures, it weakens its claim to moral authority especially when it speaks about constitutionalism at the national level.

A Leader Who Has Done It All

President John Dramani Mahama’s political journey is unparalleled in Ghanaian history. He rose patiently and legitimately through every rung of public service: assembly member, Member of Parliament, deputy minister, cabinet minister, Vice President, and President. He is the only Ghanaian leader to have experienced the full arc of democratic fortune: winning power, losing it, and regaining national leadership through the ballot.

There is dignity in completeness. Few leaders anywhere in the world are granted such a comprehensive political life. Even fewer have the opportunity to decide for themselves how it ends.

Mahama himself has, on more than one occasion, publicly indicated that he would not seek to extend his time beyond what democratic norms allow. In politics, words matter especially when spoken by those who understand how fragile trust can be. To reverse such a declaration would not merely invite criticism; it would raise doubts about whether any commitment, however solemn, can survive the temptations of power.

History is kind to leaders who know when to step back than to those who are persuaded to stay one term too long.

The Constitution: Flawed, But Firm on Term Limits

Ghana’s 1992 Constitution is not a sacred scripture. It is a living document, amended before and capable of further improvement. There is broad consensus that some of its provisions deserve reconsideration. Term limits, however, should not be among them.

Term limits are not about punishing good leaders; they are about protecting societies from their own weaknesses. Once a country begins to adjust tenure rules for sitting or recently serving leaders, no matter how popular the door opens for less benevolent actors to do the same. What begins as a lawful amendment can quickly become a dangerous habit.

In Sub Saharan Africa especially West Africa, this pattern is well known. Constitutions are rewritten, protests erupt, trust collapses, and eventually democracy itself becomes negotiable. Ghana has been spared this fate precisely because it has treated term limits as a red line.

Changing that line, even through proper legal channels, would send a signal far beyond Ghana’s borders and not a reassuring one.

Regional Stability and the Weight of Example

Ghana’s democracy is not just a national achievement; it is a regional anchor. In a sub-region frequently shaken by coups, constitutional manipulation, and electoral violence, Ghana’s greatest export is not cocoa or gold it is credibility.

Every constitutional choice Ghana makes is studied, copied, and sometimes distorted by its neighbors. A move that appears to weaken democratic restraint at home could embolden anti-democratic forces elsewhere. Stability is not preserved by force; it is preserved by example.

The cost of unsettling that example would be far higher than any short-term political gain.

Leadership and the Citizens’ Trust

Ultimately, democracy rests on a simple but fragile contract: citizens entrust leaders with power, believing it will be exercised on their behalf rather than exploited for personal longevity. Leaders, in turn, are expected to model restraint, not test the limits of public patience.

When citizens look to leadership, they are not merely seeking policies; they are seeking direction, moral as much as political. To stretch rules, reinterpret commitments, or normalize exceptions risks teaching the wrong lesson: that power, once attained, should be held onto for as long as the law can be persuaded to allow it.

That lesson is corrosive. And it is one Ghana cannot afford.

John Dramani Mahama’s legacy is already secure. Preserving it may require not another campaign, but a conscious refusal to run one. In democratic history, that is often the hardest and most statesmanlike choice of all.

GHANA MUST WORK AGAIN

Leave a comment